Single Hook Modifications for the Miramichi

Along with a complete c/r fishery in New Brunswick for Atlantic salmon of all sizes we have a regulation for 2015 requiring the use of single barbless hooks. We could endlessly debate the necessity for either of these new rules, but they are now the law, and we must work with them and still enjoy our salmon fishing. If nothing else it is undeniable that the barbless hooks will save the lives of thousands of parr every summer resulting in at least a few of these returning to the river years down the road as adults.

Thinking about the barbless requirement took me back through my years of fishing to circa 1978 when I began crushing the barbs on a big wooden swimming plug called the “Danny Deep Diver” that I used for striped bass in Maine’s Kennebec River. The plug had two huge treble hooks in the forward and middle positions, and an equally big single hook with bucktail located at the tail. Very few of the bass we caught were hooked by tail hook which showed me that they were turning on these wooden herring and trying to take it head first. Most of the time the front hook was embedded in the jaw hinge. I trolled for these big stripers among the ledges and tide rips of the Kennebec with 50 pound-test wire line and a heavy mono leader. Even with bass that averaged 40 pounds the contests rarely lasted 10 minutes. The big fish came alongside beaten, but still full of life. Reaching down with cotton gloves, and finding my moment, I grabbed them by their thick, rope-sized lower lip. I dared not release my grip for an instant for fear of getting hooked by the rest of the razor sharp points that were slashing about with every shake of the head. All hell broke loose when the fish felt my hand close around its jaw, and it attempted to twist and roll its way to freedom. In all of the hundreds of these great fish that I released I never lost my grip. I knew what the consequences might be.

Now was the time to extract the hooks. I hauled the bass out of the water and laid them across the full transom of my 24’ Aquasport inboard/outboard. I laid a soaking-wet towel over the fish’s eyes, and quickly worked out the hooks. Then I slipped an American Littoral Society tag through the fish in back of the anterior dorsal fin, and in seconds it was back in the water. We had a few short strikes, but normally, when we had a solid hook up the fish was boated. Striper stocks were crashing, and in my concern for them I looked for anything I could do to decrease release mortality. Occasionally I had some difficulty getting the big trebles out of the jaws of the bass. I had read about crushing the barbs, so I gave that a try. Immediately I noticed two things: first the fish were very definitely easier to unhook, but along with that I went from landing virtually every solidly hooked fish to losing a good percentage of them. I accepted that as a price to be paid for the easy unhooking and therefore “conservation benefits” and I still do.

By the late 1980s stripers were coming back, and in that time I had become a devotee of fly fishing. Among my discoveries were the Jim “Teeny” styled sinking tip fly lines made for West Coast salmon and steelhead fishing. Allowed to sink for a few seconds these heavy lines put our large striper flies down into the feeding zones of the cow bass. The 4 /0 singe hooks that we used had large barbs, and yanking them back out of a fibrous lip or jaw hinge could be difficult and often required pliers. Again I tried crushing the barbs, and with the same results: easier releasing, but more fish lost. To try and combat my increased losses on the barbless singles I began to copy the concept of the Alaskan circle hooks which were designed not as a conservation tool, but oppositely were invented to maximize the per-hook catch in the long-line fishery for halibut. Circle bait hooks had a very radical design that was, well, circular with the point of the hook seemingly pointed in a direction away from the fly line’s angle of pull. At first glance it was hard to imagine how anything could be hooked by this product, but for the purpose designed they worked phenomenally well. That purpose, though, was to hook halibut on a stationary long line, where the fish take the bait well into their mouth then turn direction and head for bottom. The circle hook won’t catch inside the mouth, but instead migrates to the jaw hinge and securely hooks the fish in that high-strength location. In spite of hours of twisting and turning on the line the hook stays in place. But this was not fly fishing.

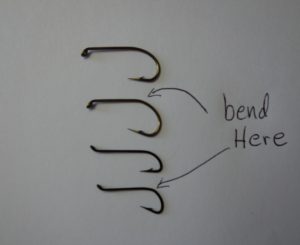

I needed the holding power of the circle, which had to be literally screwed out of the fish’s jaw, yet I wanted a design that would stick in the fish’s mouth more or less instantly on the strike. The compromise was found in what I called the “conservation bend”. We simply bent our hooks to achieve a wider more circular pocket that we hoped would hold better as the fish tried to escape. There are lots of designs like that now, a good example being the freshwater bass stinger hooks used in making large poppers. I believe that this design will land more hard-fighting fish than the normal shallow pocket of conventional J-hooks which rely on their barb to hold them in place. Unfortunately I have not seen anything like this made for tying Atlantic salmon flies. I’ve attached here a photo of two salmon hooks that I have bent to get the deeper, wider pocket that I am talking about. You will see from the directions on the photo that I position the pliers to bend the hook at the end of the shank just as the hook’s manufactured bend starts. This effectively broadens the hook bend but leaves the gap the same or even narrower depending on how much you bend.

The second and fourth hooks down have the deep pockets bend and the uppers are the originals. The top hook is a down-eyed sproat type often used for green machines, and the bottom is small, conventional salmon iron for traditional wet flies.

Note that you will occasionally break a hook making these bends. Some offshore made black salmon irons are very brittle and cannot be bent reliably. You will just have to try them to see. In preparing to write this I also googled up what I could find on going barbless for Atlantic salmon. One article talked about crushing the barb by positioning the pliers parallel to the hook point instead of perpendicular to it. The article claims that the perpendicular hold stresses a narrow area at the tip of the hook and can cause the whole point to break off. I have had that experience. My own personal preference, though, is not to use pliers, but to use forceps and position them carefully so that I am bending the barb from the tip. I bend it just enough to close the barb. The leaves the hook smooth for the intended purpose of easy unhooking but doesn’t stress and weaken the whole tip of the hook. Photo here.

As we begin the season I will probably bend some of the flies already in my inventory, but more often will bend the hooks first and then tie some new flies with them. In any case, I will have a selection of flies equipped with these modified hooks ready for the June fishing!